The Professionalization of College Athletics

The Box Score

This article traces the professionalization of college athletics. This is a complicated story, so both the Box Score summary and Complete Game are longer than usual.

The early years of college sports looked a lot like they do now: athletes were paid (although under the table and not nearly as much), repeatedly transferred schools, and critics were outraged.

From 1956 to 2014, the NCAA enforced strict amateurism rules that limited an athlete’s compensation to a full-ride, grant-in-aid scholarship covering tuition, room and board, and books.

Important Legal Background. In general, U.S. workers are covered by federal antitrust laws or union labor laws, but not both.

U.S. antitrust law, particularly the Sherman Antitrust Act, protects workers against wage fixing (i.e., paying someone less than the market will bear). College athletes have been covered by antitrust law since the mid-2010s.

If employees form a union, they are protected by the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), which relaxes antitrust restrictions. Professional athletes are covered under union labor laws.

Over the past decade or so, the Courts have repeatedly ruled that the NCAA violated antitrust law by acting as an illegal monopoly that fixed athletes’ wages at $0. As a result, college athletes can now…

Make unlimited money from endorsements, known as Name, Image, and Likeness (NIL).

Receive pay directly from their college or university.

Transfer as many times as they’d like.

College athletes now enjoy the freest free agency in American sports. Here’s why…

College sports are currently covered by U.S. antitrust law, meaning any restriction that negatively affects players’ pocketbooks is likely illegal. This is very different from the situation of professional athletes, who have unions and engage in collective bargaining with owners. That means professional sports leagues have policies—e.g., salary caps, drafts, and multiyear contracts—that would be currently illegal in college sports under antitrust law.

We are at a crossroads in college sports. Here are the possible roads forward:

The status quo.

We’ll look at the House settlement in depth, but here, the important thing is that it allows colleges to pay their student-athletes up to $20.5 million per year.

Athletes can make unlimited money from NIL deals.

Athletes can transfer as much as they’d like.

The House settlement is currently being challenged in Court on antitrust grounds.

College sports become even more professionalized.

A Court may rule the House settlement violates antitrust law because it sets a ceiling on how much athletes can be paid. If that happens, then athletes could then earn unlimited money from their college and NIL deals while transferring as much as they’d like.

Congress provides college sports with a modified antitrust exemption.

This would grant college sports governing bodies immunity from antitrust lawsuits, enabling revenue-sharing caps, NIL restrictions, and transfer limits.

College athletes become university employees and engage in collective bargaining.

This, as we will see, would be a mess.

THE COMPLETE GAME

Everyone wants to know why their college quarterback is a millionaire and drives a Lamborghini. But to understand that, you’ll first need a history lesson and a crash course on labor law.

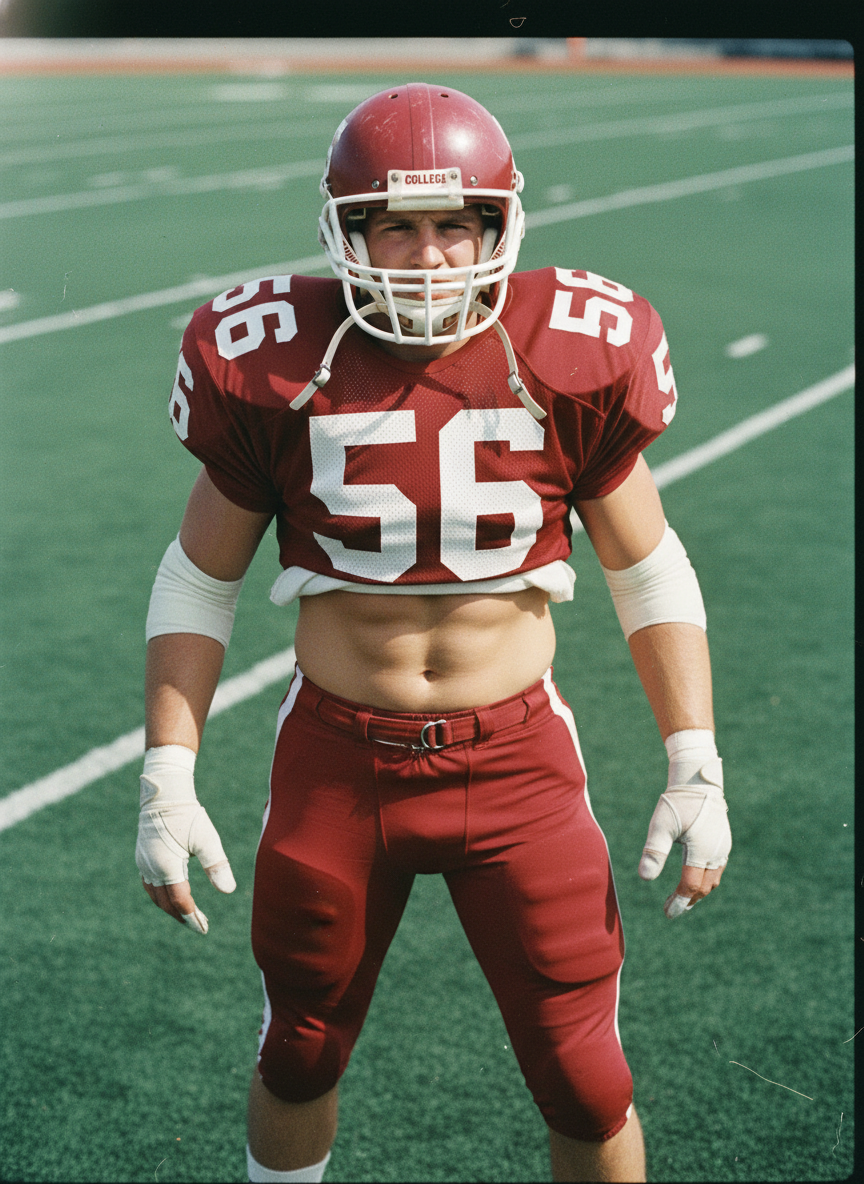

There is no getting around the fact that the professionalization of college sports is a complicated story with a lot of moving parts, and this article reflects that. To help us along, we’ll follow different versions of Jimmy, Hypothetical College’s All-American middle linebacker, through the ages (you can get a short summary of this story at The Evolution of the College Athlete.

As we trace the evolution of college athletes, I want to highlight two main themes. The first is that the chaos we see in college sports isn’t new. Commentators are fond of calling today’s college athletics “the Wild West,” and, in some ways, that’s a fitting metaphor. Today’s college sports seem like a lawless frontier, where the old sheriff—the NCAA—has been run out of town on a rail. But in other ways, the metaphor is misleading because it implies a more orderly past than college sports deserve. A better way to see it is to think of three eras: Wild West I, The Sheriff Years, and Wild West II. We’ll explore these eras below, with a bit of help from Jimmy.

The second argument is that governmental intervention can both create and solve problems in the sporting world. The current Wild West II version of college athletics was caused by the Courts and exacerbated by state laws. The government created a problem, and, ironically, only the government can solve it. Of course, whether the professionalization of college athletics is a “problem” that needs solving is a matter of opinion (you can learn more about this debate in “Should College Athletes Be Paid?”). But let’s set that aside for now as we mount up and take a ride through the Wild West of college sports.

The Wild West I: 1852-1956

The Wild West (ver. 1.0), 1852-1905

Today’s problems are essentially the same ones that have existed since the very first intercollegiate competition—a rowing match between Harvard and Yale in 1852 featuring professional ringers who attended neither school. As author Murray Sperer put it in his book College Sports, Inc.:

“Thus, in the very first college sports contest in American history, two elements were at play: The event was totally commercial, and the participants were cheating. The history of intercollegiate athletics has gone downhill from there.”

There was no governing body for collegiate sports until 1906, so each college set its own rules on eligibility, amateurism, and recruiting. Colleges exercised little oversight over their athletic departments, with elite schools—Harvard, Princeton, Chicago, and Michigan—being the worst offenders. The result was that college athletics was rife with ringers, pay-to-play schemes, and so-called “tramp athletes” who repeatedly transferred schools to get the best deal.

A Carnegie Foundation report had this to say about college athletics at that time:

“The accusations against athletics…included charges of “over-exaggeration,” demoralization of the college and of academic work, dishonesty, betting and gambling, professionalism, recruiting and subsidizing, the employment and payment of the wrong kind of men as coaches, the evil effects of college athletics upon school athletics, the roughness and brutality of football, extravagant expenditures of money, and the general corruption of youth by the monster of athleticism.”

Sound familiar?

There was also little in the way of on-field rules. As I discuss in “The AAU and NCAA’s Battle for Control of Amateur Athletics,” there was no standard rulebook for college football—the home team set its own—and little regard for player safety. As a result, college football was a blood sport. That year, Teddy Roosevelt called university presidents and coaches to the White House and told them to clean up the game or else. Out of that meeting came the modern rules of football and the organization that would eventually become the NCAA.

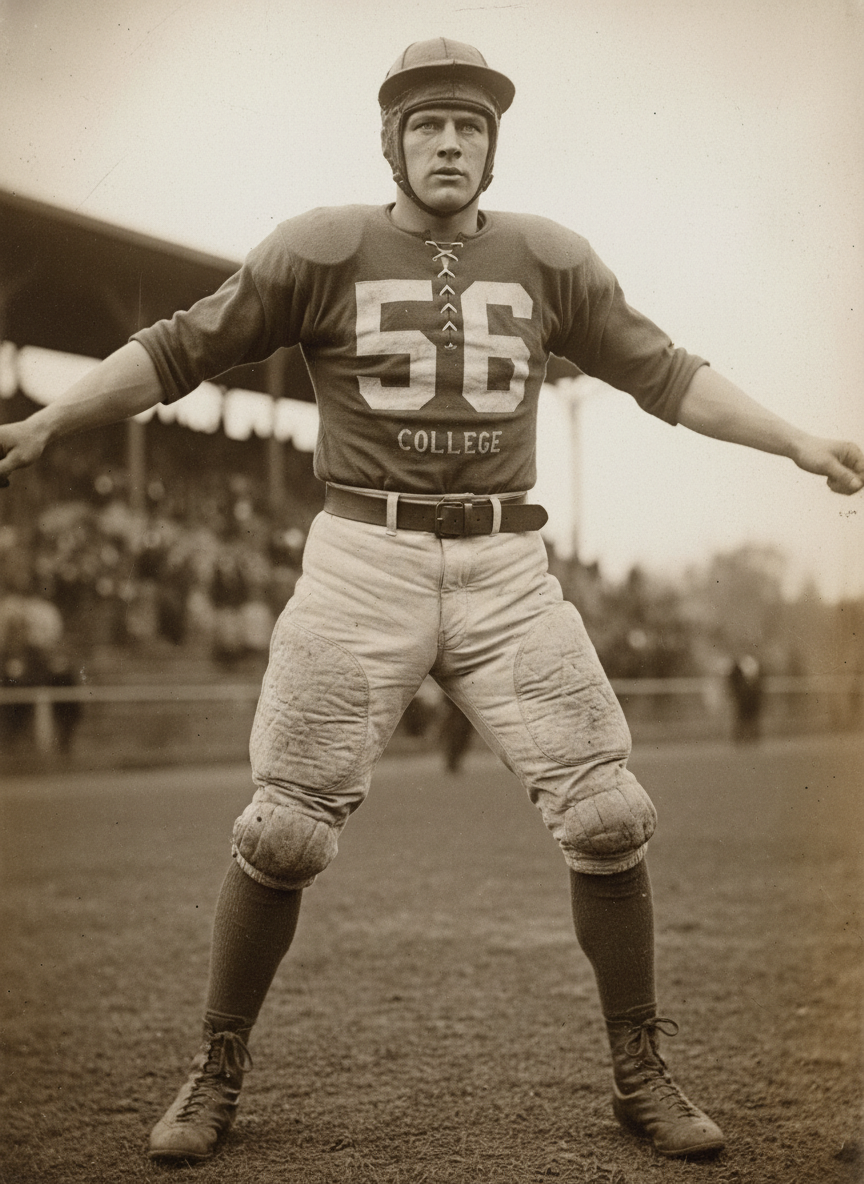

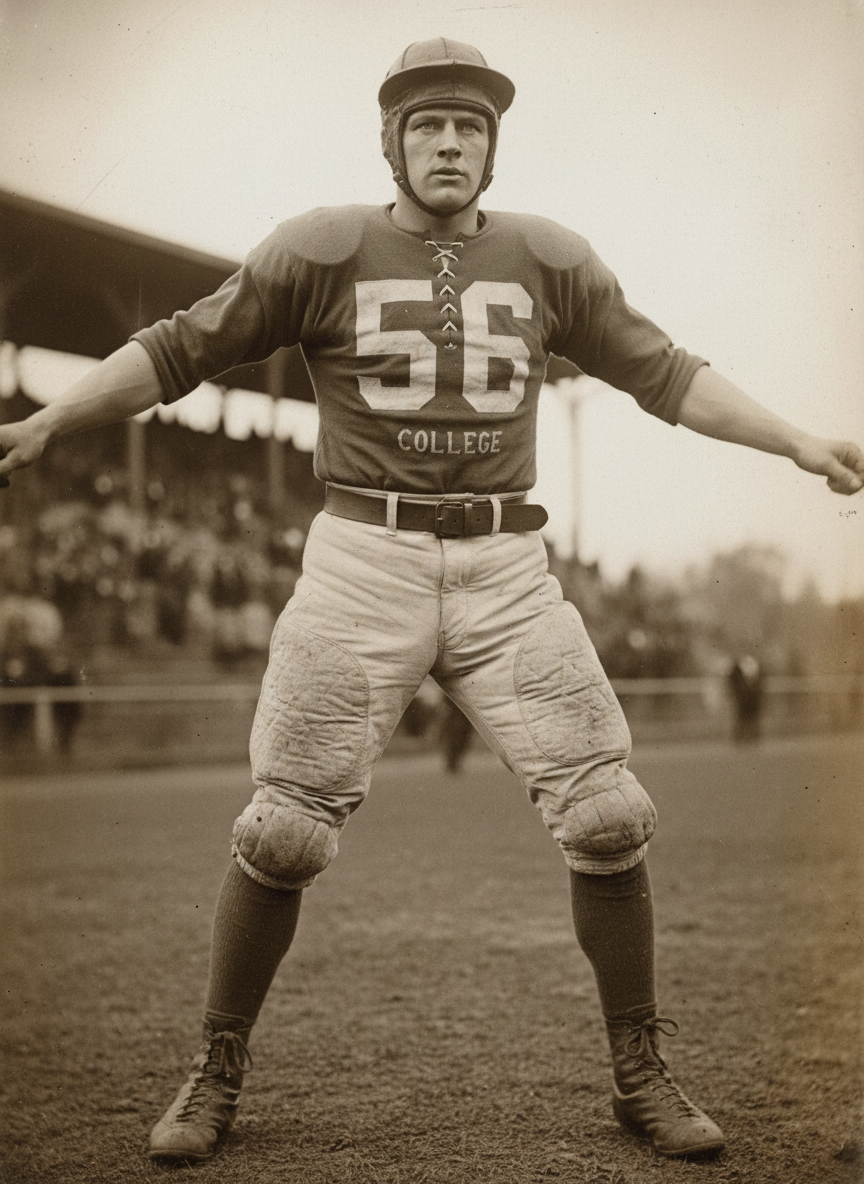

The Wild West (ver. 1.0), 1904. This is Jimmy, an All-American middle linebacker at College. Age 29; chain smoker. Transferred four times before arriving at College. Once poked out an opponent’s eye, but wasn’t penalized because eye poking was not against the rules. On paper, College has a strict amateurism policy that does not allow for athletic scholarships. In practice, College never collected Jimmy’s tuition bill, and his coach gave him a few bucks each week. Jimmy also enjoyed free steaks and beer at Joe’s Diner, and reportedly earned $10 a week from a notorious mobster. In a game against College’s hated rival, University, Jimmy mysteriously whiffed on a tackle, resulting in a University touchdown that covered the spread. Despite rarely going to class, Jimmy graduated College with a degree in economics. He went on to become a U.S. Senator.

The Wild West (ver. 1.1), 1906-1951

The Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States (IAAUS) was founded in 1906 and rebranded as the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) in 1910. In the Wild West (ver. 1.1), the NCAA did a good job putting on national championships and setting on-the-field rules for sports. However, it was powerless to enforce off-field rules regarding player eligibility, amateurism, transfers, or anything else on the business side of sports.

The initial bylaws, set in 1906, prohibited any payments or scholarships to athletes, except for need-based financial aid. Colleges ignored these rules. Boosters lined the pockets of the best players. Tramp athletes went from school to school in search of the best deal. And as college athletics became big business, schools increasingly subordinated academics to athletics, building stadiums instead of libraries and giving athletes grades they didn’t earn.

The crux of the issue, then, as it is now, is that effective regulation of college sports is a collective action problem, where the rational pursuit of self-interest leads to bad outcomes for everyone.

To illustrate the collective action problem in college sports, imagine you are a college president trying to rein in your successful but out-of-control football program. You plan to reallocate a large part of the football budget to academics, using the $800 million earmarked for a new stadium to build libraries and hire the best professors. You will also require players to attend classes and vow to stop boosters from handing them sacks of cash.

As a college president, you are in big trouble if others don’t follow suit. If you are the only one holding the line, your football team can’t recruit, and your best players transfer. Soon, your team sucks. Alumni stop giving money, fans stop showing up, and prospective students enroll elsewhere. Now that the money has dried up, everyone from the billionaire donor to the campus librarian is calling for your head.

(Lest you think I’m overselling this point, I encourage you to read “Donors Pushing Around School Presidents? Higher Education Has Become College Football.” )

As you can see, there isn’t much incentive for college presidents to crack down on football, even if they want to. While few college presidents would say so out loud, most would nod in agreement with former University of Oklahoma president George Cross when he said, “I want to build a university of which the football team can be proud.”

That, in a nutshell, is the collective action problem of college sports. While it is good for all colleges to abide by rules, there is no incentive for any one school to do so.

The solution to any collective action problem is to create an organization that can make and enforce rules, and, for college sports, that institution was the NCAA. But there were two problems. First, for the NCAA to be effective, colleges had to give up power, which they were loath to do. Second, an effective NCAA requires a delicate balancing act with rules. If its rules are too weak, the old problems persist; if they are too strict, the NCAA becomes tyrannical.

The problem with the Wild West (ver. 1) system of college sports was that member colleges did not give the NCAA sufficient power to make and enforce rules, so all the old problems persisted. The NCAA’s 1948 “Sanity Code” is a case in point. The NCAA wanted to get serious about amateurism, so it issued rules prohibiting colleges from giving athletic scholarships and requiring athletes to carry a minimum GPA. The “Sanity Code” was so unpopular with colleges that the NCAA had to repeal it a few years later.

The NCAA is powerless if colleges refuse to abide by its rules, which lies at the heart of both the old and new Wild West versions of collegiate sports. However, there are two important differences between then and now:

1. In the Wild West (ver. 1), the NCAA was undermined by its own member institutions. That is, colleges prevented the NCAA from showing any teeth. By contrast, college athletes’ effective use of the Courts has brought about the Wild West (ver. 2).

2. In Wild West (ver. 1), there was a consensus that college athletes should be amateurs. Colleges might have quibbled with the definition of “amateur” or objected to the NCAA’s punishment for violating the rules. Still, there was never any sense that college athletes ought to receive a share of the revenue they generated. In the Wild West (ver. 2), there is an emerging consensus that college athletes should be professionals.

The Wild West (ver. 1.1), 1949. This is Jimmy, an All-American middle linebacker at College. Age 25, World War II veteran, married with two kids. Jimmy attends College on the GI Bill, which pays his tuition and fees and provides a monthly living stipend. College also gave Jimmy a no-show job that pays $50 a week. The coaches and boosters also slip Jimmy a little money now and then. Many of Jimmy’s teammates have athletic scholarships, despite the NCAA’s ban on the practice under its “Sanity Code.”

The Sheriff Years: 1951 to 2014.

For many of us old timers, what I call “the Sheriff Years” seems like “normal college sports.” This was a time when college athletes were amateurs, transfers were rare, and everyone played four years. It was also an era when the NCAA ruled college sports with an iron fist.

But the “Sheriff Years” were not the norm; they were the exception.

The Sheriff Years (ver. 1.0): 1951 to 1984.

In the early 1950s, a new sheriff came to town in the form of a reinvigorated NCAA, armed with two big guns.

The first big gun was Walter Byers. Byers was a 29-year-old assistant sports information director when the NCAA hired him to become its first national director. No one expected much, but Byers eventually became one of the most influential people in the history of American sports. At his hiring in 1951, the NCAA had only one other full-time employee and did little besides put on a basketball tournament. By the time he left in 1988, the NCAA had a full-time staff of 143, a budget of over $100 million, and a massive rulebook with an investigative unit that struck terror in the heart of every athletic department.

The NCAA’s second big gun was television. From 1952 to 1983, the NCAA controlled all college football and basketball television contracts. The billions of dollars in television revenue meant growing economic and political power for the NCAA.

Still, Byers and the NCAA could not have cleaned up town without a bit of help from the mob. In 1951, players from the reigning NCAA men’s basketball national champion, The City College of New York, and seven other colleges became embroiled in a point-shaving scandal. The connection between college basketball and organized crime was so alarming that college presidents and athletic directors gave the NCAA the power it needed to clean house.

Herein lies the critical distinction between the Sheriff and Wild West years: the NCAA now had the power to solve the collective action dilemma by telling colleges what to do and punishing rule-breakers. College sports quickly became orderly, but dictatorial.

In 1956, the NCAA established rules that came to define college sports for the next 60 years. The grant-in-aid system was a four-year athletic scholarship that covered tuition, room and board, and books. Athletes had five years to play four seasons, with their clock starting on their first day in college. Athletes could use their “redshirt” year—a year when they were ineligible to compete—to get better, rehab an injury, or sit out after transferring. Speaking of transfers, athletes could not do so without their school’s permission. If they did transfer, they had to sit out a year or move down a division (e.g., from a Division I school to a Division I-AA school).

NCAA rules prohibited scholarship athletes from receiving money and gifts from their schools or boosters, working during the academic year, or making money off their name, image, or likeness (NIL). The prohibition against athletes’ use of their NIL meant they could not appear in advertisements, sell autographs or memorabilia, or receive royalties from television or video games. Violating these rules meant ineligibility for the athlete and sanctions for the school.

The NCAA tweaked these rules over the next several decades. Colleges complained that athletes could keep their four-year scholarship even if they quit the team, got injured, were insubordinate, or just plain sucked. In 1967, the NCAA said colleges could drop athletes’ scholarships if they quit the team. In 1973, the NCAA limited the scholarships different sports could offer and changed them all to one-year renewable. Coaches loved the change because they could unload the deadwood from their roster, but it wasn’t so great for injured or underperforming athletes.

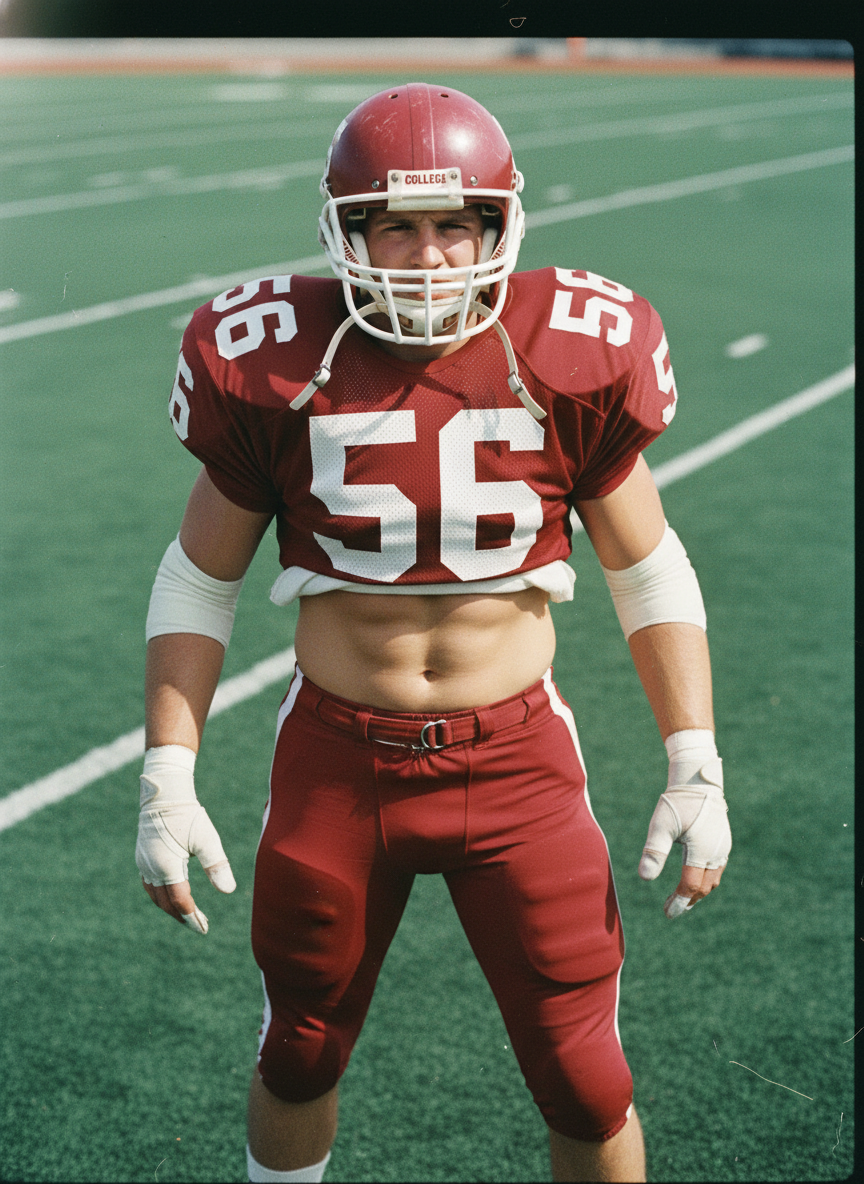

The Sheriff Years (ver. 1.0), 1975. This is Jimmy, College’s First-Team All-American middle linebacker and an Academic All-American. Despite his reputation as a hard hitter, Jimmy is a nice guy and a good student. Has a one-year renewable full-ride scholarship that covers tuition, room and board, and books. Jimmy almost didn’t make it past his freshman year; College’s Head Coach thought Jimmy was too skinny to play linebacker and wanted to yank his scholarship and give it to someone else. Jimmy’s high metabolism means he constantly eats, which is a problem since his scholarship only covers three meals a day. Jimmy needs a chemistry tutor and lab equipment, but his scholarship doesn’t cover either. He doesn’t even have enough money to put gas in the car. Slick Jim, the big money booster for College, once tried to hand Jimmy a sack of cash. Jimmy knows the penalty for accepting booster money, so he returns it. Jimmy’s parents travel to see his games because College is rarely on television.

The Sheriff Years (ver. 1.1): 1984-2014.

The first chinks in the Sheriff’s armor came in the mid-1980s as colleges began to question the NCAA’s monopoly power. In the early years of television, all sports leagues, including the NCAA, were concerned that fans would stay home to watch games on TV rather than attend games in person. So, the NCAA signed exclusive contracts with ABC and CBS, limiting the number of televised games to 14 per season. A group of football powerhouses, including Oklahoma and Georgia, tried to sign their own deal with NBC. The NCAA threatened disciplinary action against the renegade colleges, who responded by suing the NCAA.

In NCAA v. Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma (1984), the Supreme Court ruled that the NCAA acted as an illegal monopoly by pooling television contracts and limiting coverage. Although the decision seemed like a blow to the NCAA, it was a blessing in disguise, at least for a while. The Court held that while the NCAA could not act as a monopoly for television contracts, it could act as one toward the athletes. In a footnote in the majority opinion, Justice John Paul Stevens wrote:

In order to preserve the character and quality of the “product,” athletes must not be paid, must be required to attend class, and the like. And the integrity of the “product” cannot be preserved except by mutual agreement; if an institution adopted such restrictions unilaterally, its effectiveness as a competitor on the playing field might soon be destroyed. Thus, the NCAA plays a vital role in enabling college football to preserve its character, and as a result enables a product to be marketed which might otherwise be unavailable. In performing this role, its actions widen consumer choice -- not only the choices available to sports fans but also those available to athletes -- and hence can be viewed as procompetitive. P. 468 [Footnote 24]

Simply put, Stevens’ opinion provided legal cover for the NCAA to insist that its athletes be amateurs and punish any violation of those rules.

The Sheriff Years (ver. 1.1): 1987. This is Jimmy, an All-American middle linebacker for College during his junior year. Known as Jimbo. Sports a mohawk. Jimmy had a one-year renewable, full-ride scholarship that covered tuition, room and board, and books. Suspended by the NCAA during his sophomore year for steroid use. Had a fantastic junior year, and his parents watched most games on cable television. The summer before his senior year, Jimbo was spotted driving a brand new Camaro and wearing huge diamond earrings. A subsequent NCAA investigation found Jimbo had impermissibly accepted money and gifts from a booster and suspended him for his final season. Jimbo left College for the pros, but not before a profanity-laced tirade against the NCAA.

The Wild West Part II: 2014 to Present

As we will see, the mid-2010s mark the beginning of the end of the NCAA-as-Sherriff era. If the NCAA was John Wayne standing his ground from 1956 to 2014, it is now Don Knotts beating a shaky retreat.

The Wild West (ver. 2.0): 2014-19

What ran the Sheriff out of town was, of all things, a video game.

In 2009, former UCLA forward Ed O’Bannon discovered that EA Sports was using his avatar in NCAA Basketball 09 without his permission or compensation. Recall that under the grant-in-aid system, NCAA student-athletes relinquished all NIL rights in perpetuity. O’Bannon sued the NCAA, EA Sports, and the Collegiate Licensing Company for violating the Sherman Antitrust Act.

In August 2014, District Court Judge Claudia Wilken ruled in favor of O’Bannon, finding that the NCAA’s amateurism requirements violated antitrust law by fixing athletes’ earning potential at $0. In September 2015, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld most of Wilkens’ ruling but struck down a provision that would have established a $ 5,000-per-year trust fund for athletes. The decision prompted similar lawsuits, which were consolidated into In RE: NCAA Grant-in-Aid Cap Antitrust Litigation. In 2019, Judge Wilken once again presided and ruled that the NCAA violated antitrust laws by capping the value of scholarships.

Although Wilken’s decisions were narrowly tailored—they did not immediately grant college athletes the right to be paid on the open market or make NIL money—they were important in two respects.

First, they cast serious doubts about the constitutionality of the NCAA’s amateurism requirements.

Second, her ruling held that student-athletes could receive scholarships covering the full cost of attendance. Recall that the old grant-in-aid scholarships covered tuition, room and board, and books. That’s it. No gas, laundry, or Taco Bell money; no money for tutors, lab equipment, or studying abroad. The new “full cost of attendance” scholarships offered student-athletes a modest stipend for those things, but there was considerable variation in how colleges calculated “full cost.” For the ACC’s 2015-16 season, Florida State offered an extra $6,018 a year while Georgia Tech only provided $2,000.

The Wild West (ver. 2.0): 2016. This is Jimmy, an All-American middle linebacker at College, 2016. He has a four-year, full-cost-of-attendance scholarship that covers tuition, room and board, books, and a $500 monthly stipend. Jimmy thinks the whole deal is pretty sweet, though he cannot help wondering why College is making millions off him while he’s getting thousands in return. He thought about transferring to another school, but didn’t want to sit out a year or move down to an FCS school.

The Wild West (ver. 2.1): 2019-21

Emboldened by the O’Bannon decisions, many states began crafting laws to legalize NIL. On September 30, 2019, California passed the Fair Pay to Play Act, allowing athletes to earn endorsement money. The California law gave its colleges a tremendous competitive advantage: why go to Georgia on a full-ride scholarship when you can go to USC and make millions? To remain in the game, other states soon passed their own NIL laws.

The other sea change in college athletics was the Transfer Portal. Launched in October 2018, the Portal is an online database where athletes can announce their availability to transfer without needing their school's permission. Undergraduate transfers still had to sit out a year of competition or move down a division, but graduate transfers were immediately eligible to play. We’ll return to the Portal in a bit.

This Wild West (ver. 2.1) is notable in several respects. First, state law was now driving the evolution of college athletics as much as the Courts. Secondly, the patchwork of state laws made things very messy. It is hard to say college sports are on a level playing field if 50 states have 50 different NIL policies. For example, playing at Missouri, a state with generous NIL laws, could net a top recruit considerably more money than, say, playing at Mississippi.

The disparity in state law prompted then-NCAA president Mark Emmert to testify before the U.S. Senate, urging Congress to enact a uniform law regulating NIL. But before Congress could respond, the Supreme Court delivered a knockout blow.

The Wild West (ver. 2.2): June 2021 to November 2023

Sometimes in boxing, the knockout blow comes before the final punch. For the NCAA, that penultimate blow was Alston.

On June 21, 2021, the Supreme Court ruled in Alston v. NCAA that the NCAA violated the Sherman Antitrust Act by limiting the educational benefits that schools offered their student-athletes.

On its face, the Alston decision might not seem particularly noteworthy. For instance, the ruling does not say players can be paid or receive NIL money. Nevertheless, the decision was monumental in several respects.

First, it upheld the District Court’s ruling that the NCAA acted as an illegal monopoly.

Second, it overturned the precedent set by the Board of Regents (1984), which allowed the NCAA to restrict athletes’ compensation to a grant-in-aid scholarship.

Finally, the Alston decision strongly suggests the NCAA will lose any future case before the Court. The Court’s unanimous opinion doesn’t bode well for the NCAA. Even more ominous was the concurrent opinion written by Justice Kavanaugh, who stated, “the NCAA’s business model would be flatly illegal in almost any other industry in America.” In short, the Alston case sealed the fate of amateur college athletics.

There are two main features of Wild West (v. 2.2): NIL and The Portal.

NIL. Nine days after the Alston decision, the NCAA issued an “interim” policy that largely left NIL compensation up to school policy and state law. However, the NCAA said that NIL money could not entail “pay-to-play,” meaning that endorsement money could not (a) be used by a college or a NIL collective (explained below) to recruit in high schools or from the Portal, (b) be given directly by colleges to their athletes, or (c) contractually obligate an athlete to play for a particular college, let along play well. This all sounds fine in theory, but, as we will see, it is unworkable in practice.

NIL collectives are third-party organizations, created and funded by alumni and boosters, that offer endorsement deals to athletes. During the Wild West (v. 2.2), these collectives were to be independent, third-party organizations that did not coordinate with a college. And the most important thing to remember is that these NIL collectives cannot issue pay-to-play contracts.

Immediately, there were problems.

First, NIL contracts sure looked like pay-to-play schemes. Consider the case of quarterback Nico Iamaleava and the Spyre Sports Group, which manages the University of Tennessee’s NIL collective. In 2022, Iamaleava flew on a booster’s private jet on a recruiting trip to Knoxville and then signed an $8 million deal with Spyre, and all before signing a Letter of Intent to play for Tennessee. That certainly seems like pay-to-play. Nevertheless, Spyre argued that their signing of Iamaleava had nothing to do with him playing for the Volunteers; Spyre would have us believe they would be just as happy if he played for Alabama. Yeah, right. The NCAA would eventually investigate the deal, which, as we will see, was a big mistake on their part.

Second, if NIL deals are not “pay-to-play,” then a contract presumably can’t hold a player to a school or include performance clauses. Consider the case of Nico’s younger brother, quarterback Madden Iamaleva. In January 2025, Madden signed a $500,000 NIL deal with Arkansas’s EDGE collective, which included a clause requiring him to repay 50 percent of the contract’s remaining value if he left the Razorbacks before one year. Four months later, Madden left Arkansas to join Nico at UCLA; EDGE is currently suing him for breach of contract. But if NIL contracts are not “pay-to-play,” then EDGE doesn’t seem to have much of a legal leg to stand on. How can you sue an athlete for leaving a school when the contract cannot legally bind that athlete to that school in the first place?

Third, the NCAA’s prohibition on using NIL deals to recruit violates antitrust law. Imagine you’re coming off your senior year in high school as ESPN’s top-rated wide receiver. You’re heavily recruited and know you’ll sign a lucrative NIL deal. The problem is you don’t know anything about that deal until after you’ve signed a Letter of Intent. You’re getting a raw deal in two ways. First, you might unwittingly sign with a school that pays less NIL money than a rival would. Second, the NCAA’s rule effectively eliminated a bidding war for your services, which leaves a lot of your money on the table.

Fourth, many of the early NIL deals seemed fishy because they were endorsement deals with little actual endorsing. Sure, some college athletes featured heavily in companies’ marketing campaigns, including Quinn Ewers (Dr. Pepper), Shedeur Sanders (Nike), and Livvy Dunne (Vuori). But many others earned NIL deals that provided little actual value to the company and amounted to no-show jobs.

The Portal. The NCAA also instituted the “one-time transfer” rule in 2021, which allowed student-athletes to transfer schools and be immediately eligible without sitting out a year. However, they could only transfer once in their career. As we will see, this rule didn’t last long.

Both the NCAA’s NIL and transfer Portal rules were challenged in court, which leads us to the next version of the Wild West II.

The Wild West (ver. 2.2), 2022. This is Jimmy, an All-American middle linebacker at College. As one of the highest-rated recruits of the Class of 2021, Jimmy knew he would make a lot of NIL money, but he didn’t know how much because the NCAA prevents colleges from discussing those deals with recruits or athletes in the Portal. Turns out, College’s NIL collective gives Jimmy $1 million per year, which is less than he would have made elsewhere. He’s thinking of entering the Portal because he is underpaid, but he needs to choose wisely because he only gets to transfer and immediately play once in his career.

The Wild West (ver. 2.3): December 2023 to December 2025.

Everyone agreed that the Alston case rocked the NCAA. The question was: how long could it stay on its feet? The answer: not long.

The problem for the NCAA is that virtually any rule it tried to enforce violated antitrust law. So, the NCAA was constantly getting crushed in Court.

Consider NCAA losses on four crucial fronts.

1. NIL. While the NCAA left most NIL rules to states, conferences, and universities, it banned using money to recruit high schoolers or athletes in the Portal. That was about to change.

Remember Nico Iamaleava? In 2024, the NCAA investigated whether Tennessee and its NIL violated pay-to-play rules in their recruiting of Iamaleava. Attorneys General from Tennessee and Virginia immediately filed suit, claiming the NCAA’s rule violated antitrust law. The NCAA eventually settled the lawsuit after it looked like it would lose in Court. Boosters can now offer prized recruits lucrative NIL deals, but the no “pay-to-play” rule is still in effect. If you think that last part sounds strange and stupid, you’re right (more on this later).

2. The Transfer Portal. Recall that in 2021, the NCAA implemented a rule allowing athletes to transfer and play immediately, but only once during their careers.

In December 2023, U.S. District Judge John Preston Bailey ruled that the “one-time” rule violated antitrust law. A few months later, the NCAA approved new rules permitting athletes to transfer as many times as they want.

The chaos of unlimited transfers is arguably the worst part of the Wild West version II. It is frustrating for coaches and fans to see their best players leave for greener pastures at the first sign of success (e.g., quarterback Fernando Mendoza leaving Cal for Indiana, then winning the Heisman). One wonders how you could ever build a team. At least professional sports teams can sign players to multi-year contracts; in college sports, it’s often one-and-done.

3. Paying College Athletes. If Alston was the knockout blow for the NCAA’s amateurism rules, the House settlement was the punch that sent it to the canvas.

House v. NCAA was a class action lawsuit that consolidated two other pending cases (Hubbard v. NCAA and Carter v. NCAA). The plaintiffs, former college athletes who played before the NIL era, argued they deserved compensation for lost revenue stemming from the time when the NCAA acted as an illegal monopoly. They also argued that colleges should share revenue with athletes moving forward.

In May 2024, the NCAA settled with the plaintiffs; in June 2025, Judge Wilken approved that deal. Here is what the House settlement does:

Provides $2.8 billion in back pay for athletes.

Only athletes who competed at a Division I school after 2016 are eligible for compensation.

The cost of the settlement is shared by the NCAA (40%), the Power Four conferences (40%), and non-Power Four conferences (20%).

Allows colleges to share revenue directly with their student-athletes.

Colleges can now pay their athletes directly.

The revenue-sharing cap is 22 percent of Power Four revenues. It is estimated that the figure will be around $20.5 million for the 2025-26 season and will rise or fall with revenue.

Colleges don’t have to pay their athletes.

Colleges can decide who gets the money and how much; money does not have to be shared equally between sports or athletes.

Athletes can sign NIL deals on top of any money they get from their school. This approximates the professional model, with college money acting as a “salary” and NIL money as “endorsements.”

The “old-school” benefits athletes receive—e.g., tuition, room and board, and books—are still available but are not counted toward the revenue-sharing cap.

Imposes some regulations on NIL.

Any NIL contract worth more than $600 must be reported to a third-party clearinghouse.

Creates a new governance structure.

The new College Sports Commission (CSC) will enforce rules on the business side, including NIL, revenue sharing, and roster limits.

The NCAA will continue to enforce eligibility, academic, and competition rules.

Replaces scholarship caps with roster limits.

One of the more controversial proposals in the settlement is to limit the number of roster spots for each team. The concern is that roster limits mean the end of walk-ons and many non-revenue sports.

4. Eligibility. Under the NCAA’s long-standing “five-year rule,” athletes had five years to play four, with their clock starting on their first day in college. Several developments mean that this rule is on its last legs.

First came the COVID exception that created a blanket waiver for the 2020-21 academic year.

Then, several federal courts ruled that the NCAA could not count junior college toward the “five-year rule,” thereby allowing Vanderbilt quarterback Diego Pavia and others to gain additional years of eligibility.

Finally, several pending cases could end the NCAA’s eligibility rules once and for all. The athletes argue that if they can make money playing college sports, then eligibility rules are an illegal restraint of trade. They have a point: you don’t see term limits in any other field outside politics. It’s not like the American Medical Association tells its doctors, “You can only be a surgeon for four years, then go find yourself another job.”

The Wild West (ver. 2.3), 2024. This is Jimmy, an All-American middle linebacker at College. Jimmy will get a sixth year of eligibility because (a) a recent court injunction said his clock didn’t start during his two years at junior college, and (b) everyone got an extra year because of COVID. He has a full-ride, full-cost scholarship, but that really doesn’t matter since he makes $1.2 million in NIL deals. He’s considering transferring to State because its booster collective offers upwards of $2 million to top players. He was also considering turning pro, but he makes more money in college than he would on an NFL rookie contract.

Legal Challenges to The Wild West (ver. 2.3).

Dozens of pending or impending lawsuits could usher in a new version of college sports. The two biggest questions are whether the House settlement violates antitrust law and/or Title IX.

Does the House settlement violate antitrust law? This is a complicated story, so bear with me.

Remember that athletes are protected either by antitrust laws or by union labor laws, but not both.

If athletes form a union—and all major U.S. professional sports leagues have unions—they are then covered by the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) and engage in collective bargaining with owners. If not for the NLRA, collective bargaining agreements would always violate antitrust laws. On the players’ side, unionization increases bargaining power and results in higher average salaries. For owners, collective bargaining means anticompetitive business practices, like salary caps. Players’ unions and salary caps don’t exist in a free market world governed by antitrust law.

The problem with the House settlement is that the NLRA does not cover college athletes. Instead, by virtue of the precedent set by Alston, college athletes currently enjoy the full protection of antitrust law.

Why does this matter? If the Alston precedent is followed, then any restriction on athletes’ employment is likely an antitrust violation. Consider that the House settlement’s revenue-sharing agreement is essentially a cap on player salaries. Now, this would be fine if negotiated through collective bargaining between a college players’ union and the NCAA. But college athletes don’t have a union, so the NLRA does not apply. Instead, the Sherman Antitrust Act is the relevant law, and according to its terms, a revenue-sharing cap sure looks a lot like wage-fixing. Imagine, for instance, that Ohio State football and basketball players could make a combined $50 million on the open market. Capping their compensation at $20.5 million limits their earning potential.

The legal question here is an interesting one: Can the Courts carve out an antitrust exemption for college sports? Antitrust exemptions are usually the domain of Congress, and we’ll look at efforts to pass such a bill. But in this case, it was Judge Wilken’s acceptance of the House settlement that provided the exemption. If a future Court upholds the House settlement, then we’re stuck in the Wild West (v. 2.3) until Congress decides to do something about it. But if a future court strikes down the House settlement, then college athletics would become even more professionalized. Here’s why…

If antitrust laws apply fully to college athletics, there can be no limit on how much colleges can pay their athletes, no restrictions on NIL money, and no limits on the Portal. Contrast this with American professional sports, which have salary caps (except MLB), multi-year contracts, and drafts.

Does the House settlement violate Title IX? There are two types of lawsuits on this question—one that looks back, and one that looks forward.

One set of lawsuits argues that the House settlement’s $2.8 billion in backpay violates Title IX because 90 percent is going to football and men’s basketball players.

Another set of lawsuits looks forward and argues that the revenue-sharing arrangement in the House settlement is bound to favor men’s sports, thereby violating Title IX.

Regardless of timing, both suits argue that the House settlement violates Title IX's proportionality requirement. Title IX does not say that colleges have to spend the same amount on men’s and women’s sports, but it does say that athletic scholarships must be proportional to the participation rates in varsity athletics (e.g., if 60 percent of the athletic department is female, then women’s sports should get 60 percent of the scholarship money). Moreover, there must be equitable treatment of men’s and women’s sports. That means, for instance, that a men’s basketball team can’t have brand new basketballs and shoes while the women’s team plays with rubber Volts and in old school Chuck Taylors. The question, then, is whether paying college athletes fits with Title IX’s equity requirements.

Judge Wilken was clear that the House settlement was an antitrust case, not a Title IX case. Whether that rationale holds up in a future Court is a different question.

The Future

As I write this on Christmas 2025, we sit at a crossroads for college sports. Here, the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come offers us four visions of the future.

The Wild West (ver. 2.4).

In this scenario, the Courts uphold the House settlement, and a fragile status quo emerges that looks a lot like the Wild West (ver. 2.3). This includes,

Revenue-sharing agreements that allow colleges to pay their athletes directly, subject to a cap.

Additional NIL money that cannot be used for pay-to-play.

Unlimited times in the Portal.

The continuation of the “five-year rule,” which doesn’t include junior college years.

The Wild West (ver. 2.4), 2030. This is Jimmy, an All-American middle linebacker at College. Jimmy has been in the Portal three times. College pays him $250,000 per year, and he earns $1.2 million in NIL deals. Jimmy is a great collegiate middle linebacker, but doesn’t project well in the pros because he is undersized. He would like to stay at College or transfer to another school, but his eligibility is up after this year. Jimmy has sued the NCAA/CSC for its “five-year rule,” claiming it is an illegal restraint of trade. The case is currently pending

The Wild, Wild West (ver. 1).

This is the crazy, add-a-bunch-of-Wilds-to-the-West scenario. Here, future Courts strike down the House settlement, and Congress fails to act. That would open a floodgate of antitrust lawsuits that the NCAA and CSC would, by virtue of the Alston precedent, undoubtedly lose.

Here’s what might happen:

There is no limit to how much colleges could pay their athletes since revenue-sharing caps are a form of “wage fixing.”

NIL money turns into “pay-to-play.”

The NCAA could no longer enforce eligibility requirements because those rules are also illegal restraints on trade. That means…

No more “five-year rule.” College athletes could have careers spanning decades.

No more NCAA academic requirements, like a “minimum 2.0 GPA,” or “12 units per semester.”

College athletes would be considered “independent contractors,” not “student-athletes” or even “employees” (we consider the last point in depth below). Just as the NCAA cannot require the HVAC technicians who service college campuses to take 12 units per semester and maintain a 2.0 GPA, it cannot require college athletes to meet academic requirements.

Of course, individual colleges or conferences could still set academic standards as terms of employment. There is nothing in antitrust or employment law that says companies cannot place reasonable demands upon their employees. If you want to be a lawyer for Kirkland & Ellis, for instance, you have to wear a suit, work long hours, and show up to meetings. Similarly, if you want to play for Stanford, you might actually have to go to class and carry a decent GPA.

The issue with colleges setting their own academic standards is that we run into the same collective action problem that plagued the Wild West (ver. 1.1), 1906-1951. If Stanford sets high academic standards for its athletes but Cal doesn’t, then The Farm will start losing players and games to The Weenies.

The demise of non-revenue sports.

If college athletics is a business, then we should expect that, like any other business, sports that don’t turn a profit will go under. This is especially true since colleges will have to pay their football and basketball teams astronomical salaries to compete in the professional world of college sports. That will lead to…

The demise of college sports outside the SEC and the Big Ten.

According to one study, only 18 of the 229 NCAA Division I programs turned a profit. Every one of those schools competed in the SEC or the Big Ten.

If colleges have to pay athletes at fair market value, their bottom lines will only get worse.

If no team outside of the SEC or Big Ten has a chance to compete for national championships, fan interest will start to dry up. Why have college sports if your team can’t win and no one cares (see UCLA football)?

Eventually, colleges will begin to wonder why they are sponsoring professionalized sports teams that lose money and have no educational value.

The demise of women’s athletics.

As discussed earlier, a legal battle is looming in college sports over antitrust versus Title IX. Either sports are a free market governed by antitrust law, or they are an educational activity that mandates gender equity. They can’t be both.

While women’s college sports are becoming more popular, they still take in a fraction of the revenue generated by football and men’s basketball.

Given the current Supreme Court configuration and the fact that the Court’s composition is unlikely to change anytime soon, the betting odds show antitrust as the prohibitive favorite over Title IX.

The eventual demise of the Power Two.

I suspect the SEC and the Big Ten would expand into two superconferences.

SEC will include teams like Florida State, Miami, and Clemson.

The Big Ten will include teams like Notre Dame, TCU, and Utah.

Fan interest in college sports will dry up because (a) most fans will have graduated from schools that have dropped athletics, and (b) people will come to realize they’re just watching a minor league version of professional sports.

As fan interest dries up, so too will the television money.

The loss of revenue will eventually convince even the teams in the Big Two that college sports are no longer worth the cost.

The transition to the NCAA Division III model, or just intramurals.

Colleges may decide to adopt the D-III model, which has no scholarships. Alternatively, colleges might disband their athletic departments entirely and offer only intramural sports.

This sounds pretty good for me right now. It would place college athletics in its rightful place as something that enhances rather than replaces an educational experience.

The Wild, Wild West (ver. 1), 2030. This is Jimmy, an All-American middle linebacker at College. As a 16-year-old high school junior, College offered Jimmy a $12 million contract over four years. In addition, College’s NIL, the Booster Collective, signed Jimmy to a $20 million contract, provided he made over 80 tackles per year and didn’t transfer. As an independent contractor, Jimmy does not attend College as a student.

The Wild, Wild West (ver. 2).

In the Wild, Wild West (ver. 2), college athletes are considered college “employees.” That might not sound like a big deal—after all, many athletes are already making a ton of money from NIL deals and will soon be paid directly by their colleges. But in some ways, this scenario would be just as crazy as the Wild, Wild West (ver. 1).

If college athletes are deemed college employees, then they are covered by the myriad of federal and state laws concerning minimum wage, overtime, workers’ compensation, insurance, disability, benefits, retirement, and occupational safety. Those are all important considerations, but they pale in comparison to the most significant consequence: the possibility of unionization and collective bargaining.

If (and this is a big “if”) all college athletes were to form a nationwide union, then they could engage in collective bargaining with the NCAA/CSC. All the major questions swirling around college athletics—e.g., revenue sharing, salary caps, NIL deals, the Portal, eligibility requirements, academic standards, drug testing, workload, etc.—would be resolved through those negotiations.

There are pros, cons, and political roadblocks to treating players as employees.

The pros:

First, depending on how it is done, unionization would move college sports out of the realm of the Sherman Antitrust Act and under the umbrella of the National Labor Relations Act. The result is that college athletics would look a lot like professional sports. College athletes would be equal partners in decision-making and enjoy greater bargaining power, likely raising their average salaries. For its part, the NCAA/CSC could insist upon anticompetitive business practices—e.g., salary caps, Portal restrictions, multiyear contracts—that could preserve some semblance of a competitive balance.

Second, it would allow the NCAA/CSC to enforce rules. Over the past decade, virtually anything the NCAA has tried to do has been struck down by the Courts on antitrust grounds. The NCAA’s inability to make and enforce rules is why we call the current era the “Wild West” of college sports. Brought under the NLRA, this endless stream of antitrust lawsuits would come to an end. Once the players’ union and the NCAA agree upon rules through collective bargaining, then the NCAA could once again act as the rules enforcer that college sports so desperately need.

Third, unionization gives players a voice. One criticism of the House settlement was that it didn’t speak for all, or even most, college athletes, as evidenced by the current spate of lawsuits against it on antitrust and Title IX grounds. A deal negotiated by a players’ union, however, would carry greater legitimacy because athletes, not lawyers, had the last word.

This all sounds pretty good, but here are the cons:

First, it would be hugely expensive. Imagine if the University of Southern California treated its estimated 700 student-athletes as employees. If we limit our analysis to wages, payroll taxes, and a bare-bones health care plan, a conservative estimate is that it would cost SC an additional $33-40 million per year. That figure is on top of the $20.5 million in House revenue-sharing and whatever SC already gives in scholarships, aid, and other types of support for student-athletes. As we’ve seen, very few athletic departments enjoy a positive net revenue. Treating athletes as employees would most likely mean drastic cuts to athletic departments, especially to non-revenue-producing sports.

Second, it makes things weird. Imagine you’re a tenured political science professor at The Ohio State University, teaching POL 141: The Politics of Sports. There are several football and basketball players in your class, all of whom earn far more than you. What message does it send that the highest-paid employees of a college are not the college president or the dean of the law school, but the football coach, the basketball coach, and their respective starting lineups? It’s also weird that these players are in your class to begin with because they are employees. The Ohio State University doesn’t require the librarian, landscaper, or linebacker coach to take 12 units and maintain a 2.0 GPA. Why should athletes be any different?

Third, college sports would inevitably feature the things that drive sports fans nuts: strikes and lockouts. If a collective bargaining agreement isn’t reached, then players strike, or the NCAA locks them out. Either way, it sucks.

Finally, for those who want college sports to return to the amateur model, the goal should be the return of the student-athlete, not the emergence of the employee-athlete.

What one thinks of the pros and cons of treating college athletes as employees is academic given the seemingly insurmountable political roadblocks to making it happen. Here they are:

First, the prospects of creating a nationwide union of college athletes look dim under current U.S. law. The NLRA covers private employees, not public-sector employees. That is why all professional sports unions are covered under the law; the NFL, NBA, WNBA, NHL, and MLB are all private entities. It is also why Dartmouth men’s basketball is the only college sports team to unionize; Dartmouth is a private college. If there were a nationwide union, it would most likely consist of athletes from private schools such as Stanford, Vanderbilt, and Northwestern. It would not include athletes from public schools like California, Nebraska, or the University of Alabama. That’s a problem because collective bargaining would only cover some schools.

Second, federalism would create a mess of the athletes-as-employee model. Employment at public universities is mainly governed by state law, and states vary considerably in their rules regarding minimum wage, compensation, hours, benefits, and the right to unionize. College athletes might unionize and negotiate a pretty sweet deal in a labor-friendly state, like California. Athletes in right-to-work states, like Texas, might be out of luck. Like the early days of NIL, the result would be a 50-state patchwork of athlete labor laws that would make competitive balance a joke.

Finally, political power dynamics make unionization unlikely. The players face a collective action problem. It takes a lot of work to get a union up and going, and college athletes are busy people with other things to worry about. Moreover, unionization might mean some of the highest-earning athletes take a pay cut, which is a tough ask. While the athletes have not provided a unified front so far, the opposition has. With a few exceptions, most college presidents, athletic directors, league commissioners, and the NCAA oppose unionization. As is the case with most collective action problems, the small, wealthy group (colleges) beats the numerically larger but resource-poor group (athletes).

Advocates of unionization and collective bargaining aren’t ready to quit, and they suggest two paths forward. We’ll cover the first path here, and the second in the next section.

Tennessee AD Danny White is one of the few college administrators who like the idea of a college athletes’ union and collective bargaining. His idea is not to treat college football and basketball players as college employees, but rather as independent contractors who form a national employment organization. That organization could then engage in collective bargaining with the NCAA/CSC. Moreover, White plans to sidestep antitrust and Title IX concerns by making college football and men’s basketball its own thing. I don’t know if this would hold up in Court, but I kind of doubt it. We’ll talk about a second option for unionization in our next version of college sports.

The Wild, Wild West (ver. 2), 2030. This is Jimmy, an All-American middle linebacker at College. Jimmy is a member of the State Union of College Athletes (SUCA), which includes all of College’s athletes, as well as all of the other collegiate athletes within the state. The SUCA engaged in collective bargaining with the state colleges. Under the terms of that agreement, College pays Jimmy the maximum salary of $1.5 million per year. He also signed a NIL deal worth $1 million per year, subject to performance standards. Athletes are flocking to colleges in Jimmy’s state because its labor-friendly laws are good for the pocketbook. As a result, the “haves” and “have-nots” of college football are sorting themselves out by state.

The Sheriff Years (ver. 2).

The best chance to stabilize college sports is for Congress to act, which is a little like having Shaq on the free-throw line needing two to win.

There are two ways that Congress can “save” college sports.

The first is to provide the NCAA/CSC with a modified antitrust exemption that would stop the endless stream of antitrust lawsuits. The SCORE Act currently before Congress would do just that by allowing the NCAA/CSC to set rules on revenue-sharing, NIL, and the Transfer Portal. The Act also prevents college athletes from being classified as “employees.”

The second option, the “College Athlete Right to Organize Act,” takes the opposite approach by amending the NLRA to allow college athletes to unionize and engage in collective bargaining.

Regardless of which route is taken, either bill would go a long way toward ending the Wild West of college sports. But neither bill has a snowball’s chance in hell of passing in the immediate future.

The SCORE Act is generally supported by Republicans and opposed by Democrats. In the closely divided 119th House, the Republicans cannot afford any defectors from their ranks. Unfortunately for them, there are defectors, including Freedom Caucus members Chip Roy (R-TX), Byron Donalds (R-FL), and Scott Perry (R-PA). The GOP holdouts had a variety of concerns, from the procedural (the bill was granted a rule that did not allow amendments on the floor) to the substantive. Representative Roy had this to say:

“I don’t know what we’re doing, what the powers that we have here in engaging and interfering with states, but if we’re going to take a big federal step because the federal court intervened, and we’re going to intervene, well, then maybe we should fully intervene.

Maybe we should fix the damn mess so that we don’t have, you know, 16 teams in the SEC and 17 teams in the ACC and 19 teams in the Big 10, and freaking Stanford and Berkeley on the West Coast in the Atlantic Coast Conference, all because of money. I mean, it’s just laughable that this is anything but … a massive money grab.”

Even if the SCORE Act somehow passes in the 119th House, it has an even dimmer chance of overcoming a filibuster by Senate Democrats. As Senator Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) said, “I can pretty well guarantee the SCORE Act ain’t going to make it through the United States Senate.”

The Democrats’ “College Athlete Right to Organize Act” is DOA because the Republicans control Congress, and there is no way the GOP will vote for a bill that expands unions.

So, we are left with the familiar story about how the U.S. Congress works. It goes like this:

There is a problem.

Members of Congress all recognize there is a problem.

Members of Congress disagree on the solution to the problem and offer competing bills.

Either bill would be an improvement upon the status quo.

The minority party’s bill has no chance of passing.

The majority party’s bill could pass if…

All Republicans in the House vote for it.

Republicans can secure 60 votes in the Senate to overcome a filibuster.

However,

House Republicans can’t get all their members to vote for the bill.

Senate Republicans have no chance of getting the Democratic votes needed to overcome a filibuster.

Each party hopes to do well enough at the next election so they have the sizable majority needed to pass the bills they want.

Neither party will do well enough at the next election to pass the bills they want.

Nothing will get done, even though (a) everyone recognizes the problem, and (b) two pretty good bills could solve it.

The Sheriff Years (ver. 2), 2030. This is Jimmy, an All-American middle linebacker at College. College pays Jimmy the $350,000 maximum salary, and he makes upwards of $1 million per year in NIL money. Jimmy knows he is underpaid, but cannot sue the NCAA because college sports have a modified antitrust exemption. Jimmy can enter the Portal once in his career. Jimmy is an Economics and Business major, carrying a 3.2 GPA.

Conclusion

So, what have we learned besides the fact that I clearly don’t subscribe to the whole “writers shouldn’t mix metaphors” thing?

We are in the Wild West of college sports because any rules the NCAA tries to enforce are shot down in Court on antitrust grounds.

The Alston decision and the House settlement provided a one-two knockout punch that sent amateur college sports to the canvas.

And the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come showed a future of college sports as grim as the one he showed Scrooge.

I hope that, like Scrooge, college sports can turn things around, and I can rewrite this article with some more positive metaphors. But College Sports Stability is currently a 1000/1 underdog to College Sports Chaos. Hey, another metaphor!