The Evolution of the College Athlete

The professionalization of college sports is a complicated story; you can read the long version in The Professionalization of College Athletics.

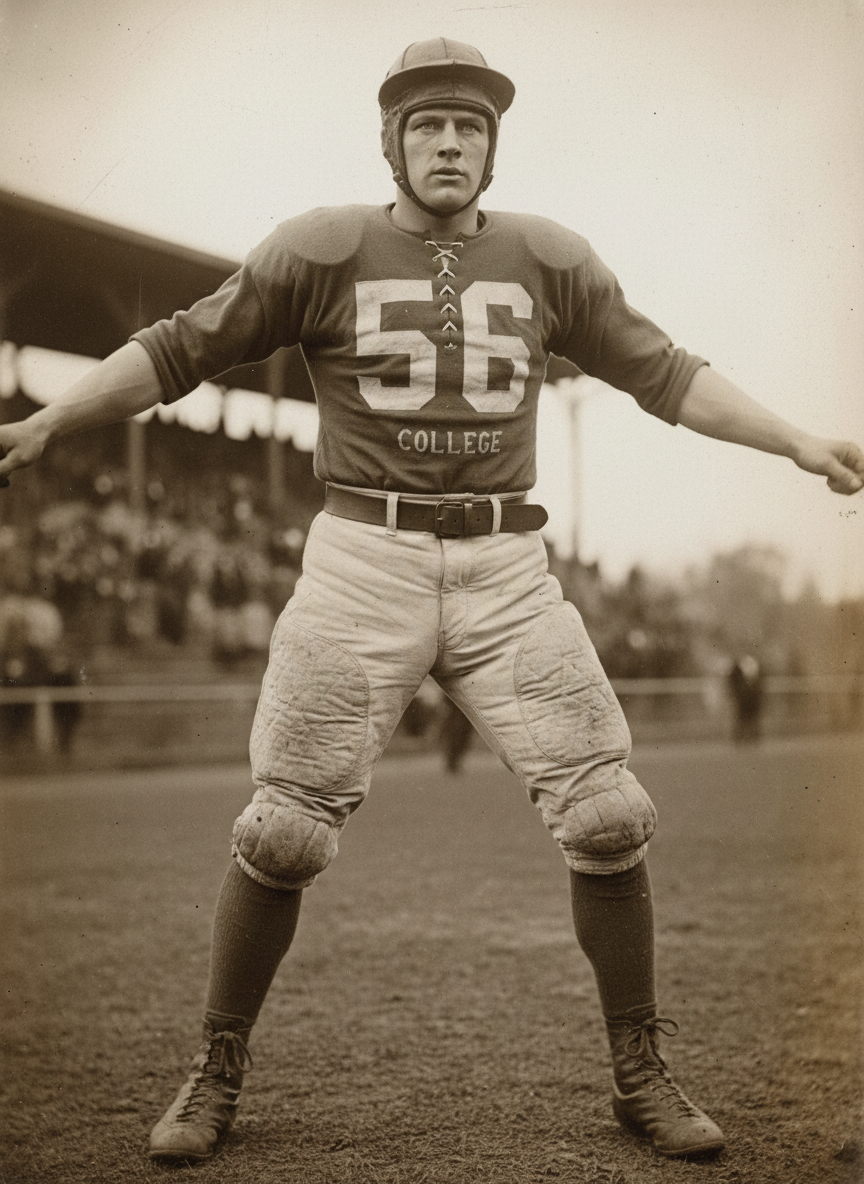

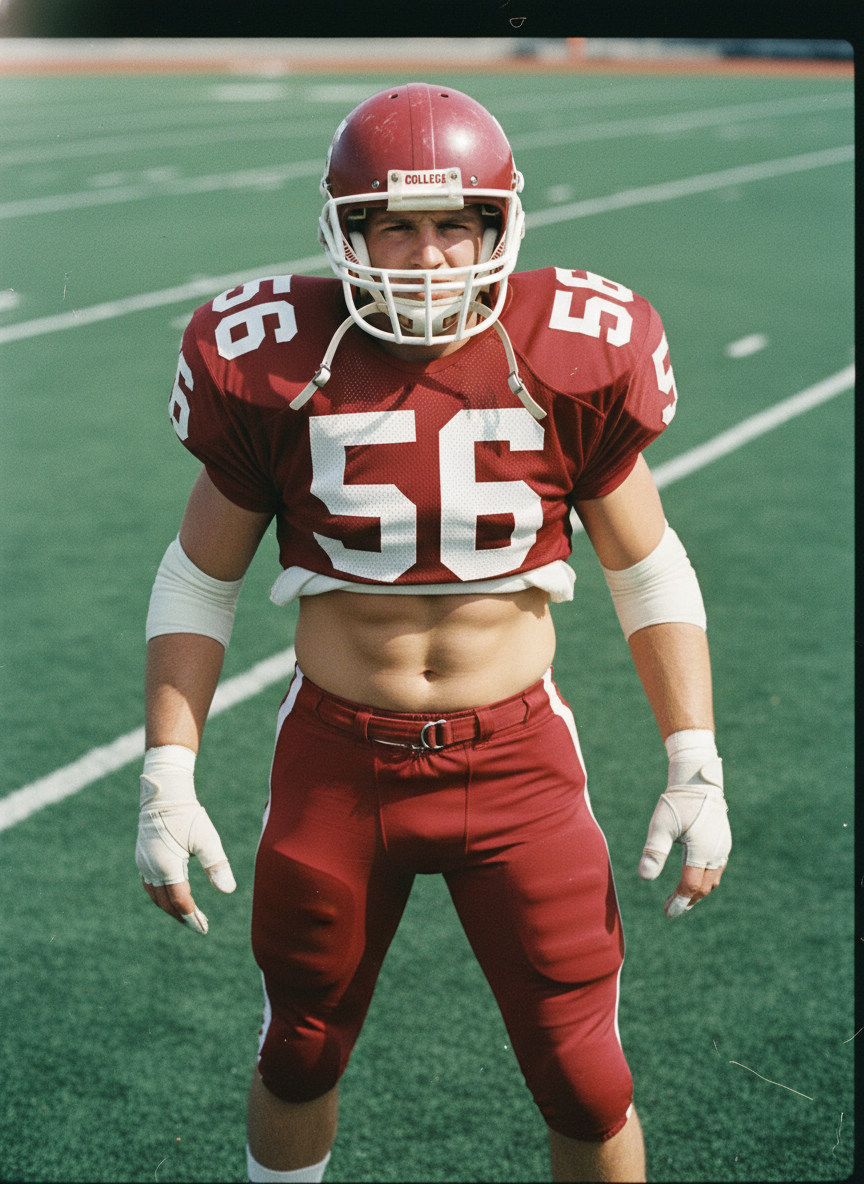

Here is the short version, as told by following College’s All-American middle linebacker through the years.

Terms

Policy changes are indicated with a *.

Grant-in-aid. Athletic scholarship covering tuition, room and board, and books. If athletes accepted a grant-in-aid scholarship, NCAA rules prohibit them from working during the academic year or from making money off their NIL (see below).

Full cost of attendance. Athletic scholarships that cover tuition, room and board, books, and a modest stipend for things like transportation, lab equipment, and additional meals.

NIL. Athletes making money from their Name, Image, and Likeness. These endorsement deals include appearing in advertisements, selling autographs or memorabilia, or appearing at corporate events.

NIL Collectives. Third-party organizations with ties to a particular college that solicit funds from donors and distribute that money to athletes in the form of endorsement deals.

Redshirting. This is a year in which players can practice but are ineligible to compete. Before 2019, players would lose their redshirt year if they played only one snap. Players redshirt for several reasons, including (a) using an extra season to improve, (b) to become academically eligible, (c) sitting out a season after transferring, or (d) rehabbing an injury. In rare situations, the NCAA would grant a “medical redshirt” to an injured player who had already burned his normal redshirt.

The “five-year rule.” Athletes have five years to play four seasons, with their clock starting on their first day in college.

The “year-in-residence” rule. This requirement meant athletes had to sit out for one year after transferring.

The “downward exception” rule. The “year-in-residence” rule is waived if athletes move down divisions (e.g., from a D-I program to a D-II program).

The “one-time” rule. An NCAA rule that waived the “year-in-residency” requirement once in a player's career.

“Pay-to-Play.” This rule prohibits colleges or NIL collectives from contractually obligating an athlete to attend a particular college or from setting performance standards (e.g., your NIL contract states you must play for Alabama; you must start 10 games; you get a $100,000 bonus for 100 tackles or more in a season).

Power Five (Four) Conferences. The most dominant football conferences, including the SEC, Big Ten, Big 12, ACC, and, until recently, the Pac-12.

Antitrust. The Sherman Antitrust Act prohibits wage fixing (e.g., saying a college athlete can’t make more than $0 while they play football).

The Portal. An online clearinghouse where athletes can announce their intention to transfer schools without their current school’s permission.

The Portal window. A set period of time during which an athlete can enter the Portal. Exceptions to this rule include when a head coach leaves the program, the school eliminates the sport, or if the athlete is a graduate transfer.

1906

Scholarship: None

Transfer: No general rules; set by each college. Frequent transfers.

NIL: None

Redshirt: None

Paid by College: No, but players are frequently paid under the table.

Eligibility: No general rules; set by each college.

Rules Enforcement: No general rules; set by each college.

Roster Limits: None

1949

Scholarship: In 1948, the NCAA issued its “Sanity Code,” which eliminated athletic scholarships. The “Code” was so unpopular with colleges that it was repealed in 1951.

Transfer: No general rules; set by each college.

NIL: None

Redshirt: Yes.* In the 1937 season, Nebraska guard/linebacker Warren Alfson wore a red jersey while practicing but not playing for the Cornhuskers, thus starting the term “redshirting.”

Paid by College: No, but players are frequently paid under the table.

Eligibility: Freshmen ineligible to play.* There are a few general rules set by the NCAA; most are set by colleges.

Rules Enforcement: Very weak NCAA enforcement; most rules set by colleges.

1966

Scholarship: Grant-in-aid, four-year scholarship.* Scholarships could not be revoked for injury, poor play, or if a player quit the team. No cap on the number of scholarships a college could offer.

Transfer: Need permission from the current college to transfer to another. The “year-in-residence” requirement meant athletes had to sit out for one year after transferring.

NIL: None.

Redshirt: Yes. Redshirting became common in the early 1960s, and the rules surrounding it didn’t change much until 2019.

Paid by College: No.

Eligibility: The “five-year rule.”* Required high school athletes to have a 1.6 GPA to be eligible.*

Rules Enforcement: Strong enforcement from the NCAA.

1975

Scholarship: Grant-in-aid, one-year renewable.* The big change is that scholarships changed from four years to one-year renewables, which could be revoked due to injury, poor play, insubordination, or quitting the team. Number of scholarships capped at 105.*

Transfer: The “year-in-residence” and permission requirements are in effect. The “Downward exception” means that transfers are immediately eligible to play if they move down divisions.*

NIL: None.

Redshirt: Yes.

Paid by College: No.

Eligibility: Freshmen eligible to play.* Revoked 1.6 GPA rule; athletes had to graduate high school.*

Rules Enforcement: Strong enforcement from the NCAA.

1987

Scholarship: Grant-in-aid, one-year renewable. Number of scholarships capped at 95.*

Transfer: The “year-in-residence,” permission, and “downward exception” in effect.

NIL: None.

Redshirt: Yes.

Paid by College: No.

Eligibility: NCAA drug testing.* Incoming freshmen needed a minimum 2.0 GPA and a minimum score of 700 SAT or 15 ACT.*

Rules Enforcement: Strong enforcement by the NCAA. However, the NCAA v. Board of Regents (1984) decision ruled that the NCAA could not act as a monopoly over television contracts, making college football financially independent of the NCAA.

1992

Scholarship: Grant-in-aid, one-year renewable. Number of scholarships capped at 85.*

Transfer: The “year-in-residence,” permission, and “downward exception” are in effect.

NIL: None.

Redshirt: Yes.

Paid by College: No.

Eligibility: Incoming freshmen needed 13 core academic classes (up from 11), and introduced a sliding scale in which a higher GPA could offset a lower test score, and vice versa.*

Rules Enforcement: Strong enforcement by the NCAA.

2016

Scholarship: Full Cost of Attendance Scholarship.* Scholarship cannot be revoked for athletic reasons.* Athletes could work during the off-season, but their income was capped at $1,200 to $2,500 per semester.* Number of scholarships capped at 85.*

Transfer: The “year-in-residence,” permission, and “downward exception” are in effect. A 2006 rule change allows graduate transfers to play without sitting out a year.*

NIL: None. However, the O’Bannon v. NCAA (2015) decision suggests change is coming.

Redshirt: Yes.

Paid by College: No.

Eligibility: The NCAA eliminated minimum standardized test scores for eligibility but increased the number of core courses from 13 to 16.* Created the Academic Progress Rate and punished teams that fell below a certain standard.* Implemented the 40-60-80 rule that said athletes had to have taken 40 percent of the units needed to graduate by the start of their third year, 60 percent by the fourth year, and 80 percent by their fifth.*

Rules Enforcement: Moderate. The NCAA still enforces rules, but is beginning to lose in Court on antitrust grounds.* In 2014, the Power Five conferences became known as the “autonomy conferences” and were granted greater decision-making power to create their own rules related to scholarships and athlete benefits.* The College Football Playoff (CFP) was created in 2014 by the Power Five Conferences plus Notre Dame. The CFP is separate from the NCAA and controls most of the money and bowl games.*

2019

Scholarship: Full Cost of Attendance Scholarship. Scholarship cannot be revoked for athletic reasons. Number of scholarships capped at 85.

Transfer: Introduction of The Portal in 2018, allowing athletes to announce their intention to transfer without receiving their college’s permission.* The “year-in-residence” and “downward exception” are still in effect.

NIL: No. However, California’s “Fair Pay to Play Act,” which allows its athletes to make NIL money, was passed in 2019 and was to take effect in 2023.

Redshirt: Yes. Two big changes. 1. A player’s redshirt year isn’t lost unless they play four games or more.* Medical redshirt rules now require the injury to have occurred in the first half of the season, with 70 percent of the season remaining.*

Paid by College: No

Eligibility: No major changes.

Rules Enforcement: Moderate enforcement, but the NCAA is being weakened by Court rulings and state law.

2020

Scholarship: Full Cost of Attendance Scholarship.

Transfer: No major changes to the Portal, with the “year-in-residence” and “downward exception” still in effect.

NIL: No. But additional states passed legislation to legalize NIL, scheduled to take effect within two or three years.

Redshirt: Yes.

Paid by College: No.

Eligibility: Because of COVID, the 2020-21 is not counted toward the five-year eligibility rule.

Rules Enforcement: Moderate-to-weak. The NCAA is rapidly trying to keep up with Court decisions and state laws, all the while dealing with the disruption caused by COVID.

2021

Scholarship: Full Cost of Attendance Scholarship.

Transfer: The Portal and the introduction of the “one-time rule,” which says athletes are eligible to transfer and play immediately only once in their careers.*

NIL: Yes.* Players are now allowed to sign endorsement deals; no limits on the dollar amount an athlete can make.* The NCAA announces an “interim” policy that mostly leaves NIL up to state law and college policy, but requires that NIL money (a) is not used to recruit high schoolers or athletes from the Portal, and (b) is not “pay-for-play,” meaning NIL contracts cannot be contingent upon performance or enrollment at a particular school.*

Redshirt: Yes.

Paid by College: No

Academic Eligibility: No significant changes.

Rules Enforcement: Moderate-to-weak. In Alston v. NCAA (2021), the Supreme Court said that the NCAA violated the Sherman Antitrust Act by fixing athletes’ wages at $0. This decision severely weakened the NCAA, leading to the transfer-and-play rule and NIL deals. However, the NCAA still attempts to regulate college athletics through its “one-time” rule and NIL prohibitions on recruiting and “pay-to-play.”

2025

Scholarship: Full Cost of Attendance Scholarship. As part of the NCAA’s 2024 Core Guarantees, athletes will have expanded medical coverage, health care insurance for up to two years after graduation, degree completion funds for up to 10 years, mental health services, financial advice, and protections against scholarship cuts or reduction for performance reasons.*

Transfer: After losing a series of lawsuits, the NCAA abandoned the “year-in-residence” requirement.* Athletes are now allowed unlimited transfers, provided they are within the transfer Portal windows.*

NIL: Yes. Players can sign endorsement deals with no limits on how much they can earn. After losing a series of lawsuits, the NCAA now allows colleges and collectives to present NIL deals to recruits.* NIL money still cannot be “pay-to-play,” meaning it cannot be tied to playing for a particular college or include performance clauses. The distinction between NIL-as-endorsement and NIL-as-pay-to-play isn’t clear.

Redshirt: Yes. No major changes.

Paid by College: No. However, this is the last year before the House settlement takes effect, allowing colleges to directly pay their athletes, subject to a revenue-sharing cap.

Eligibility: Several court cases challenged the NCAA’s “five-year rule.” An injunction currently prevents the NCAA from counting junior college years toward the five-year cap.*

Rules Enforcement: Weak. In the past five years, athletes have repeatedly taken the NCAA to Court for antitrust violations and have won most of their cases. As a result, the NCAA has been unwilling or unable to enforce many rules regarding NIL, the Portal, and eligibility.

2026

Scholarship: Full Cost of Attendance Scholarship, including the NCAA’s Core Guarantees. Under the House settlement (2025), scholarship limits are replaced by roster-size limits.*

Transfer: Unlimited transfers.

NIL: Unlimited NIL money. Athletes and colleges must report deals worth more than $600 to the College Sports Commission (CSC).* The CSC has vowed to crack down on NIL deals that are more pay-to-play than actual endorsements.* This will be challenged in Court.

Redshirt: Yes. No major changes.

Paid by College: Yes.* Under the House settlement, the NCAA and its schools must provide $2.8 billion to former athletes to compensate for fixing their wages at $0.* There is also $20.5 million per-school revenue-sharing cap from which colleges can directly pay current athletes. Colleges do not have to pay their athletes, but, if they do, they can decide who to pay and how much.*

Eligibility: No significant changes from 2025, but pending Court cases could lead to significant changes in the NCAA’s long-standing “five-year rule.”

Rules Enforcement: Weak. A new governance structure has emerged in which the College Sports Commission (CSC) handles the business side of college sports, while the NCAA handles eligibility and on-field rules. It remains to be seen just how much the NCAA and CSC can regulate college sports, given the continued antitrust litigation and the reluctance of colleges to approve and abide by rules.